Emerging risks: climate risk to supply chains: have you mapped your exposures?

Dr Iain Willis, director at climate risk modelling firm TransZero, demonstrates how worsening extreme weather has the potential to aggregate business interruption risk through first and second tier global supply chains.

Businesses today rely on complex, global supply chains to stay competitive. Beyond lowering production costs, diversified supplier networks offer efficiency gains that help companies scale their operations. However, recent years have tested the resilience of these networks.

Following the Covid-19 pandemic, supply chains were slow to recover in 2021, only to face new disruptions in 2022. An ongoing Russia-Ukraine war followed by mounting tensions in the Middle East and protectionist U.S. trade tariffs have all contributed to ongoing uncertainty.

Amid this turbulence, companies are becoming increasingly aware of their supply chain exposures. In both 2024 and 2025, the annual Allianz Risk Barometer survey found that 31% of risk managers identified business interruption and supply chain as one of their top concerns.

Similarly, Airmic’s June 2025 sourcing strategy survey revealed that 64% of companies were actively measuring supplier risk exposure, with 79% of respondents having already moved to diversify their supply networks as a risk mitigation strategy.

Businesses overlooking climate risk to supply chain

While geopolitical impacts on supply chain are frequently discussed, one emerging threat to business interruption remains under-addressed: climate change. Whether through direct physical damage to a company’s premise or the cascading delays caused by losses to first and second tier supplier locations, extreme weather events are capable of triggering extensive periods of business interruption.

The past has highlighted multiple examples of extreme weather events impacting unlikely global supply chain connections and vulnerable accumulations within and across industry sectors.

In 2011, Thailand's Chao Phraya River basin was hit by severe flooding, inundating 19% of all Thailand’s manufacturing firms and resulting in economic losses of $46 billion. Industrial sites housing major electronics companies and automotive manufacturers were particularly impacted, triggering a ripple effect through global supply chains. The subsequent global delays in the delivery of cars, computer parts and other electronics underscored the large accumulation of similar industries within a small geographic area.

Vulnerable coastal regions are a concern in a changing climate, as demonstrated in 2017 as Hurricane Harvey struck the Gulf Coast of the U.S., a significant hub for oil refining and chemical production. The Tropical Cyclone brought record rainfall and storm surges that disrupted refinery and petrochemical operations, highlighting the sector’s acute sensitivity as a global export hub.

An estimated 24% of oil production in Texas had to cease in both the days leading up to landfall and immediately following. The impact extended beyond regional fuel shortages to global chemical supply disruptions, affecting industries reliant on plastics and pharmaceuticals.

The recent past has also brought into focus the compounding effect of slow-onset climate risk. In 2023, an El Niño pattern of global weather resulted in a prolonged drought over regions of Central America. Very low rainfall caused levels in Gatun lake – a feeder lake to the Panama canal – to drop below 80 ft.

Paris Agreement failure will have major implications

While extreme weather risks are not new, it is the changing severity and frequency of these events due to climate change that risk managers need to be monitoring as climate models predict many extremes such as flooding, hail, tropical cyclone and wildfire may become more commonplace and more costly to business owners around the world.

In the absence of major greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions, the world is on track to significantly over-shoot the target agreed in the 2015 Paris Agreement of limiting global warming to two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. This will have profound impacts for supply chain risk as global weather extremes shift in the future.

Climate change scientists often highlight the Clausius-Clapeyron relation which estimates that for every degree the atmosphere warms due to GHG emissions, it can hold approximately 7% more moisture. This creates a super-charged environment more conducive to climate extremes such as flash flooding.

Other trends include rapidly increasing coastal sea surface temperatures in regions such as the North Atlantic which are linked to hurricane formation and intensification. While overall hurricane count in a future climate may remain largely the same or even reduce slightly, recent research has noted the increasing potential for explosive rapid intensification, whereby a Tropical Cyclone windspeed can increase by 30 or more in 24 hours6. This phenomenon appears to be happening more often, with Hurricane Erin being the latest example.

The nature of expected changes in global climate extremes are not predicted to be equal. We expect the probability of some locations experiencing a 100-year flood to increase significantly, perhaps becoming five or ten times more likely. Conversely, a warmer climate has the potential to also increase the average length of wildfire seasons, as well as creating more conducive weather for heatwaves and violent thunderstorms that can trigger perils such as large hailstones and result in greater energy use to cool properties in the summer.

Modelling climate risk concentrations

To avoid being blindsided, companies must take a proactive stance to map and model both their current and future climate risk exposure across their entire global supply network. Today, sophisticated models are available to help businesses assess and quantify how various climate perils—from floods and hurricanes to droughts and wildfires—could cascade through their supply chains.

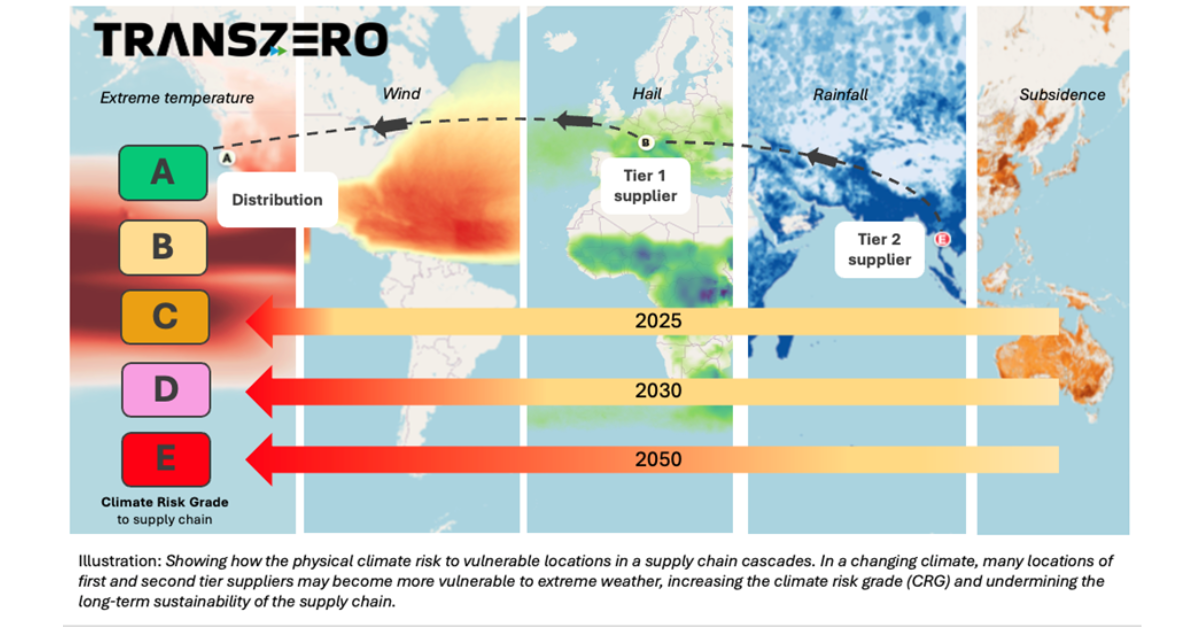

The above diagram demonstrates how the physical climate risk to vulnerable locations in a supply chain cascades. In a changing climate, many locations of first and second tier suppliers may become more vulnerable to extreme weather, increasing the climate risk grade and undermining the long-term sustainability of the supply chain.

Companies that have a thorough, data-backed understanding of where their climate vulnerabilities and concentrations sit within their supply chains will be in the strongest position to identify mitigating actions and take control of the risk.